Providing vision care and education for people with albinism

STANDING VOICE VISION PROGRAMME

Our Vision Programme enables people with albinism to achieve their educational or professional potential

Albinism causes a melanin deficiency that reduces pigmentation in the eye. People with albinism have a complex visual impairment, with altered retinal development and nerve connections to the eye. Optometry services are extremely limited in Tanzania, so the unique vision needs of people with albinism are often overlooked.

This has serious consequences for educational participation and performance. For the children with albinism lucky enough to secure secondary education, most will be unable to read from standard distances. Ensuing struggles with academic performance further ingrain stigma, and contribute to common perceptions that children with albinism do not belong in schools. Many students leave school ostracised and unskilled, facing a future of unemployment.

Our Low Vision Programme is a network of clinics, delivering low vision care and devices to people with albinism across Tanzania. The network enables students with albinism to achieve their educational and professional potential.

IMPACT

The Vision Programme is currently active in 11 regions of Tanzania

3,677 people have been screened and examined as part of the Standing Voice Vision Programme

14 optometrists trained to address the complex visual impairment of people with albinism

The Programme

LOW VISION AND ALBINISM

People with albinism have a melanin deficiency that causes complex visual impairment. In albinism, the front and back of the eye develop differently, and nerve connections between the eye and brain are altered. Albinism does not cause total blindness, although many with the condition are classified as ‘legally blind’. Persons with albinism can usually distinguish colours, but their vision will typically lack precision or detail.

Many people with albinism have nystagmus, a condition causing involuntary, irregular eye movements. These movements may be side-to-side, up-and-down, or rotary. Despite these movements, the world appears steady and unmoving. The condition occurs with varying severity in people with albinism and usually lessens with age; it is typically least apparent at their ‘null point’, a particular viewing distance at which nystagmus slows and details are clearest. For persons with albinism, the null point often occurs at about 5-10cm, when reading up close; for a few it can be found in an extreme position, with an accompanying head tilt or turn.

Most Africans have dark brown irises with high levels of melanin pigment. This serves as a natural block against damaging sunrays. Because of their melanin deficiency, Africans with albinism usually have blue, hazel or brown eyes, with greater photosensitivity and an impaired ability to absorb light. Their paler irises often have small openings around the edges (trans-illumination defects), and can sometimes appear pink due to light reflecting off blood vessels at the back of the eye. Bright light can often cause pain and discomfort for people with albinism, and sunglasses are advisable to protect against sun damage.

Albinism affects the back of the eye as well: without melanin, the retina, specifically the fovea, is underdeveloped and does not accurately process incoming visual signals. Vision is impaired as a result, with long- and short-distance details appearing blurred. Depending on the type of albinism, blurring can be mild or severe.

The optic nerve is also altered by albinism. In people without visual impairment, optical pathways from each eye enter the brain and meet in a particular way; both eyes work together to facilitate the brain to ‘see’ in 3D depth. In albinism these pathways do not develop in the same way: in some cases, one eye dominates; in others, both eyes work equally well but will not work together, so the individual must switch between them. This leads some people to develop an eye turn or strabismus.

People with albinism are of equal intelligence to anyone else, and no scientific study has ever linked the condition to impaired brain function or mental processing in any way. The complex visual impairment caused by albinism is non-degenerative, and does not worsen over time. Glasses can improve vision to a small or great degree depending on the individual, but some loss of detailed vision will still remain for people with albinism. Vision can then be enhanced and optimised by low vision devices and adjustments to lighting or seating position. With the right support, a person with albinism can thrive in the vast majority of educational and professional settings.

OUR RESPONSE

Our Vision Programme has delivered low vision care and education to people with albinism in 10 regions of Tanzania.

Our programme focuses on students with albinism in their formative years. We break the cycle of poor educational performance, unemployment, and further segregation by delivering low vision education and visual aids in schools, ensuring children with albinism do not lose out on their educational aspirations. We also deepen teachers’ understanding of albinism, arming them with the knowledge required to improve student care and combat bullying. We have now published an albinism information booklet for teachers that contains practical advice to enable teachers to help children with albinism reach their potential in school. This gives students the chance they deserve to succeed in their studies and grow as capable, confident individuals ready to prosper as valued contributors to society.

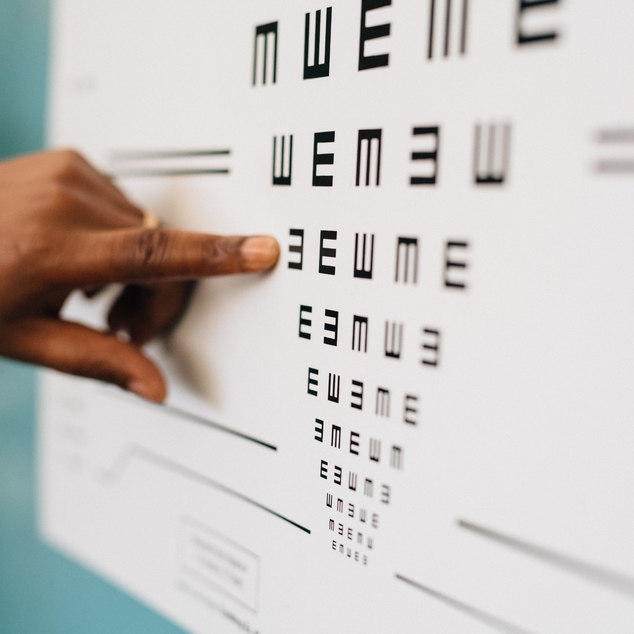

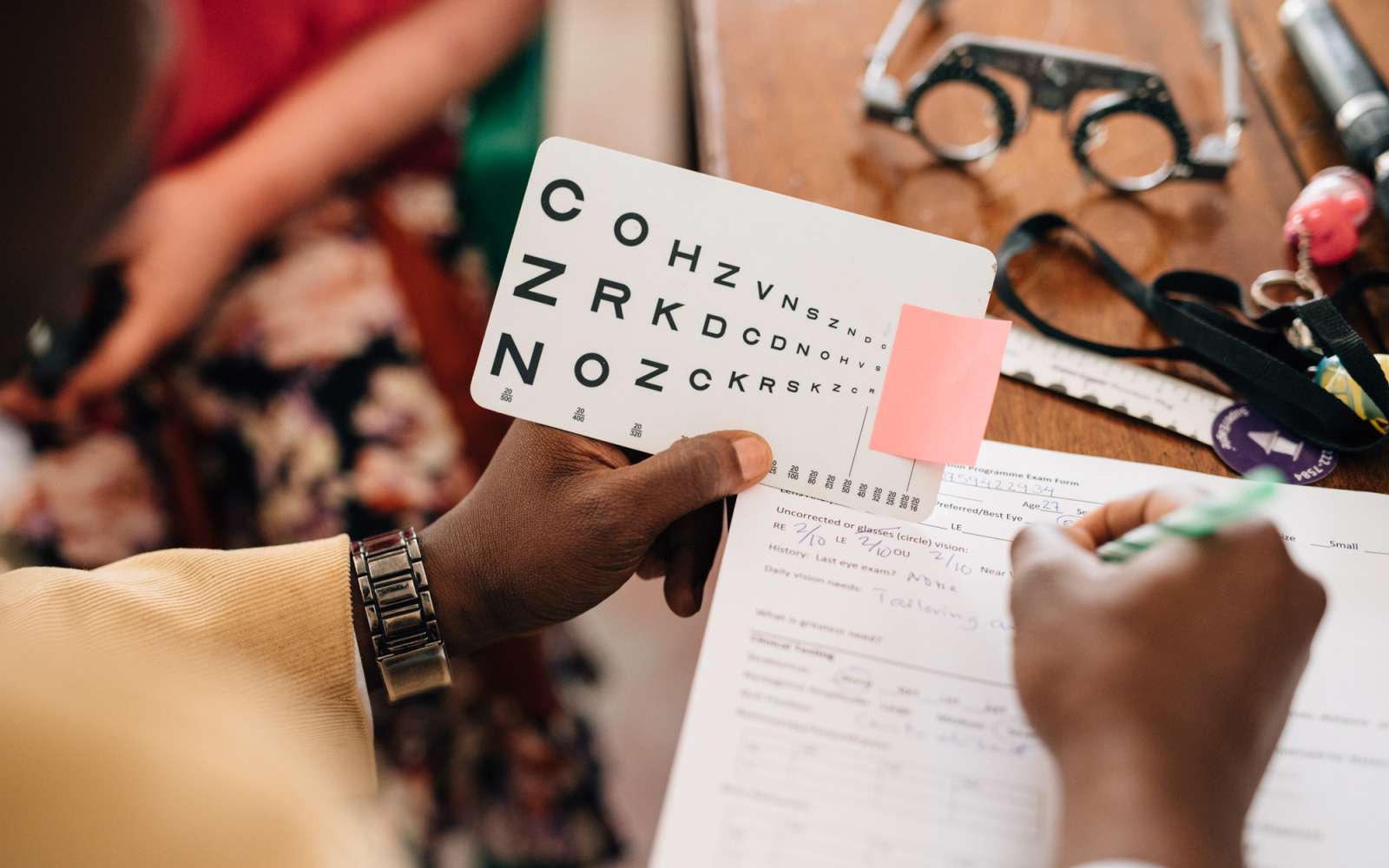

Visiting a school for the first time, we run a two-day clinic in which every child with albinism receives a low vision examination, a monocular telescope, a pair of UV-protective sunglasses, and an educational session and booklet about low vision. Of those screened, between 40-50% will typically require glasses, with our field optometrist prescribing these on site and returning to deliver them in the weeks that follow.

Initial two-day clinics are followed by six-monthly check-up visits from our Health Programmes Coordinator, who integrates any new students not yet screened and monitors the progress of those previously assisted. To measure improvements in students’ vision we record clinical data, study teacher feedback on the relevant child’s performance, and compare his or her examination results before and after our services. Monitoring continues for the rest of the child’s school career.

So far we have screened, examined and enrolled over 3,000 people with albinism on our programme and distributed over 7,000 vision devices in total. We aim to bring this service to all people with albinism in Tanzania, and replicate it internationally wherever need exists.

OUR TEAM AND PARTNERS

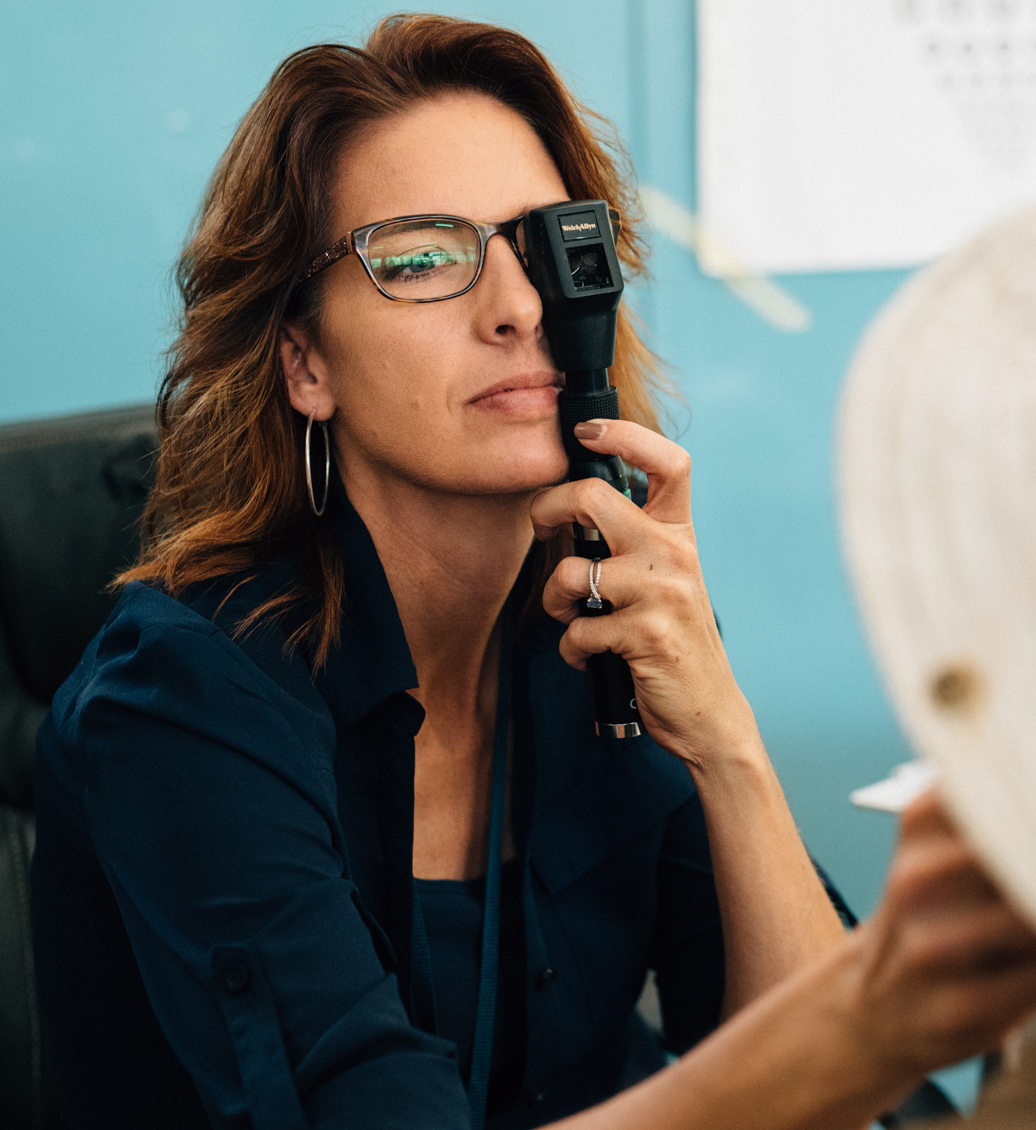

Our programme is directed by Dr Rebecca Kammer, a leading specialist in the low vision of persons with albinism. Dr Kammer trains our network of Tanzanian programme optometrists and, with the rest of the Standing Voice team, coordinates these services by mobilising the following key partners:

The Kilimanjaro School of Optometry, a training facility whose network of professionals is crucial to our service delivery

The Tanzania Optometric Association (TOA), which provides an invaluable network of in-country optometrists for us to activate in the delivery of our Programme

Schools, which work alongside us to eliminate stigma and build stronger support networks for students with albinism

The Ministry of Health, together with local authorities, which work with us to pursue improvements in health policy

Manufacturers and funders who support our clinics

Reach

Our programme has registered 3,677 patients across 11 regions of Tanzania

Impact

Patient data shows 4.3x improvement in visual acuity following our support

"Standing Voice helps us provide the necessary instruments at the right time for patients."

Dr Abdi Nyembo – Optometrist

"We have to keep doing this: we must increase the number of people with access to care."

Dr Rebecca Kammer – Vision Programme Clinical Director

"We are honoured to partner with Standing Voice to give children with albinism the care they need."

Aïcha Mokdahi – President, Essilor Vision for Life

"Good vision is a right. Good vision should also be a priority."

Jayne Waithera – Albinism Activist